A Terrific Trio

October 19, 2020College of Arts & Sciences

Diego Riveros-Iregui reviews the day’s plan with Maribel Herrera, Megan Raisle and Nehemiah Stewart. (Photo by Alyssa LaFaro)

Undergraduate researchers Chloe Schneider, Maribel Herrera and Megan Raisle, under the leadership of UNC-Chapel Hill geographer Diego Riveros-Iregui, spent two months in Ecuador’s northern Andes Mountains exploring climate change. They came back to Chapel Hill, wrote a paper that was published in a major journal and communicated their research to broad audiences.

Conducted fieldwork in the sciences. Spent two months in Ecuador after six weeks of hands-on training in Chapel Hill. Worked on a diverse team that faced multiple physical and mental challenges. Wrote a paper as female undergraduate lead authors that was published in an academic journal. Shared their research with multiple audiences. Became lasting friends.

Chloe Schneider, Maribel Herrera and Megan Raisle experienced all of those things, checking accomplishments off their bucket lists and adding valuable experiences to their resumes during their time at UNC-Chapel Hill.

“They had the perfect collective traits that you look for in student researchers — attention to detail, perseverance and curiosity — and they complemented each other really well,” said Diego Riveros-Iregui, Bowman and Gordon Gray Distinguished Professor in the department of geography who led a research expedition of five undergraduates and a doctoral student to Ecuador in summer 2019. He then spent a year mentoring Schneider, Herrera and Raisle on examining the data and writing a paper about the findings. “Working with them was a great experience, one of the greatest pleasures I’ve had as a professor in my seven years at Carolina.”

Schneider and Raisle graduated last May, and Herrera will graduate in December. All three say they are considering graduate school.

Schneider works for NASA DEVELOP, an applied sciences program which addresses environmental and public policy issues by using earth science data to help with community challenges.

Raisle works for the Environmental Data & Governance Initiative, a consortium of academics who focus on environmental justice issues and getting publicly available environmental data to states and communities. She also recently started a position as an Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education researcher in the Center for Environmental Solutions & Emergency Response at the Environmental Protection Agency.

“We have this special bond,” said Herrera, who is majoring in geography and environmental studies. “I’m so proud of us. We all put in so much work and had our own struggles in the field, but it paid off. I came through this experience being much more confident in my own resilience.”

Páramo paradox

At 14,000 feet in the Cayambe Coca Ecological Reserve in the northern Andes Mountains of Ecuador, the weather can go up or down at the flip of a coin. In this mystical place called a páramo, these high-altitude grasslands receive a lot of sun and precipitation year-round, but because of the high elevation, temperatures can drop very low.

“It’s cold and tropical, and what that does is it causes the accumulation of organic matter and not a lot of decomposition. Carbon in this ecosystem has been accumulating for thousands of years; it’s among the highest carbon stocks on the planet,” Riveros-Iregui said. “There are reasons to believe that due to global warming, some of this carbon is now being released into the atmosphere.”

Schneider can testify to the physical challenges of the páramo, where she says it was cold, rainy and foggy almost every day.

“There’s actually a volcano, Antisana, in the distance and we had one clear day about three or four weeks into the trip where we could actually see this huge snow-capped mountain,” said Schneider, an environmental science and geography major and information systems minor. “But the physical challenges also made it really memorable, and those were the parts I loved about it.”

Raisle also likes to talk about the mental challenges of being in that kind of environment, including the complexities of getting to know each other and work together as a team in the field.

“Diego was really intentional in selecting a group of folks who were diverse, not only in demographics, but in what disciplines we came from and what we were interested in and what our strengths were … those synergies can make for a great team,” she said. “But getting to know people in maybe the most challenging physical conditions of your life can be hard. That was big, and I’m really grateful he did that.”

Riveros-Iregui said for many students, fieldwork is the point where their coursework clicks, and they understand how biology and chemistry and physics are related and important.

“I really want students to struggle a little bit and to realize ‘I need to solve this problem,’” he said. “The research process is difficult and imperfect and full of challenges. There will be data you cannot explain right away, and anything can go wrong.”

Herrera said if she could characterize the experience in one word, it would be “unexpected.”

“We were in it for the long haul; you couldn’t just go back to your dorm room and say, ‘I’m done.’ It was tough,” she said, laughing. “But I loved it.”

Schneider recalls a moment on the plane trip home when a passenger commented on the equipment briefcase she was carrying and asked, “What are you all doing?”

“Maribel and I looked at each other and said, ‘We’re scientists.’”

Publishing a paper in a pandemic

After returning from Ecuador, the team spent the 2019-2020 academic year working on the paper.

Riveros-Iregui said they began thinking about what they wanted to accomplish with the research from the very beginning, formulating early on the questions they wanted to address so they were prepared to execute the plan.

Then COVID-19 hit midway through the spring semester.

“We came back with a really good dataset, and much of the writing coincided with COVID-19; fortunately we were already working collaboratively online,” he said. Still, he stressed that it is rare for undergraduates to be lead authors on a paper, and that immediately sets them apart.

Schneider said Riveros-Iregui had a bigger picture in mind, but that he let the undergraduate team have a role in shaping the research.

“Diego did not just put us in research assistant positions; he really gave us the opportunity to become scientists ourselves and to take control of the project,” she said. “It’s intimidating as an undergrad; you doubt your ability to do that. But when we dug into the data, we just found some really cool things.”

Herrera said to stay on top of time management, they tried to at least “touch” the paper every day, even if only crafting or refining a sentence or two. That way it felt less overwhelming.

“I never would have thought I could have this experience as an undergraduate. I get so emotional when I think about it,” she said. “As a first-generation student, to also have a Latino first-generation professor as a mentor was absolutely amazing.”

Raisle said Riveros-Iregui is a champion for his students, and the team’s ability to get the paper published has a lot to do with him coaching them through the process.

“It speaks to the degree to which a professor is willing to commit time to you,” said Raisle, a geography major and environmental science and studies minor. “Diego can be really tough, but at the end of the day, he advocates for his students so hard and wants you to be successful.”

After only minor revisions, “Carbon Dioxide (CO₂) Fluxes from Terrestrial and Aquatic Environments in a High-Altitude Tropical Catchment” was published in the early online edition of JGR Biogeosciences. It made the cover of the August journal.

Schneider, Herrera and Raisle are noted as co-first authors on the paper, and they insisted on adding a line that they “contributed equally to this work.”

“Women in STEM, Women in STEM”

Research, professional development and community outreach were all part of the experiences made possible by Riveros-Iregui’s prestigious National Science Foundation Early Career Award.

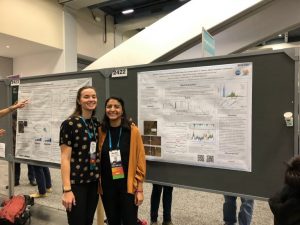

To boost their professional development, Schneider and Herrera traveled with him to present their research at the American Geophysical Union Conference in San Francisco in December 2019. That same month, Raisle attended the 25th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, also known as COP 25, in Madrid.

Once they returned to Chapel Hill, the three volunteered at the Museum of Life and Science in Durham, creating their own interactive projects for kids related to hydrology and watersheds.

When they think about all of the experiences they’ve had together, they reflect back on one time in the field in Ecuador that sums everything up.

Herrera sets the stage: It was their first night experiment, and it was raining. They were cold, dark, wet, muddy, tired. They had to retrieve data and sensors from four stations before hopping back on the warm van to head out of the páramo. The final station, located underneath a waterfall, was the hardest to reach.

“We tried to hike up the side of a slope while holding the laptop and the sensors, and we kept slipping as we tried to grab on to the grasses,” Herrera said. “We were physically drained, so we just started chanting ‘Women in STEM, Women in STEM,’ and that motivated us to keep going.

“That was a beautiful moment when we made it to the top.”

Endeavors magazine first documented the students’ Ecuador research expedition in the story “Climate Game-Changers,” and we followed up with the researchers a year later.