Research UNCovered: Esteban Agudo

September 16, 2020

Endeavors

Esteban Agudo is a doctoral student in the Department of Biology within the UNC College of Arts & Sciences. He explores how temperature affects the feeding rates of organisms living on reefs and how this impacts ecosystems like the Galápagos Islands.

Q: When you were a child, what was your response to this question: “What do you want to be when you grow up?”

A: A paleontologist. Then a zoo veterinarian. And then a biologist. Oh boy — I wanted to be a lot of different things. I was not sure about a marine biologist, though. That came later.

Q: Share the pivotal moment in your life that helped you choose your field of study.

A: In college, I was more interested in terrestrial ecology. Specifically, I wanted to work with bugs and be an entomologist. But then I joined the school diving club and started scuba diving a lot. I lived about 45 minutes from the water. One of my friends had this old pickup truck, and on Friday evenings we would load up the diving gear and tanks and get to the beach around 10 p.m. We would do a couple of nocturnal dives, sleep in our sleeping bags, and then wake up, do a couple more dives in the morning, and travel back to school at noon. That was probably the best time of my life.

Eventually, one of my school professors, who was a marine biologist, asked me if I wanted to help him with some coral reef research counting fish. But I had never done any scientific diving. He taught me how to do a fish census. We presented the results at a local scientific meeting, and after that I was pretty much hooked.

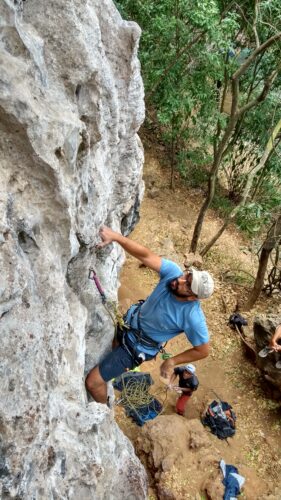

Agudo climbs with friends in Caracas, Venezuela. “I used to live about 15 minutes from La Guairita, which is one of the most popular climbing places in Venezuela,” Agudo shares.

Q: Tell us about a time you encountered a tricky problem. How did you handle it and what did you learn from it?

A: I’m from Venezuela, a country that is under a dictatorship and a profound economic and humanitarian crisis — more than 10 percent of the population has migrated in the last couple of years. I completed my undergrad and master’s degrees there, and I worked as a researcher. Doing science in a place in those conditions makes everything trickier and harder.

For example, in 2015 I traveled to the coast to work on an environmental impact study and got stuck for seven hours in my car because people were protesting in two different towns I had to pass through. And they were protesting for basic things like water and electricity — a problem that has become more and more frequent. So, an eight-hour drive turned into a 15-hour drive.

Even now, I’m facing difficulties as part of the board of the Venezuela Ecological Society. A few weeks ago, there was a big oil spill, and the government is making it hard for independent scientists to do an evaluation of the spill and possible effects. We are trying to solve this through a citizen science project asking people from affected areas to send us pictures of the beaches covered in oil and their coordinates. Using that data and satellite images, we can build a map of the spill.

These are just some examples, but they are pretty common things any biologist in Venezuela has to face, along with many other difficulties. These situations force you to learn a lot of things: to be patient and resilient, to do your best and stay positive, and to adapt to any circumstance. You learn that if you love what you do, you can find solutions to almost any problem. It also makes you think about how your research can be applied to make people’s lives a little bit better.

Q: Describe your research in 5 words.

A: Ocean warming makes fish hungrier.

Q: What are your passions outside of research?

A: Any outdoor activity. I used to windsurf, free dive, and spearfish. I also got into rock climbing in the last couple of years. And, of course, I love soccer. Right now, I spend a lot of time trail running and gravel biking at North Carolina Forest or Umstead Park in Raleigh.

Research UNCovered delves into the lives of UNC researchers from all disciplines and career levels, showcasing not only their research prowess but personal experiences in academia and beyond. Know someone we should feature? Nominate a researcher.