Helping Prepare Giant Tortoises for the Wild

October 1, 2020University Communications

A giant tortoise in the Galapagos. (Photo by Francisco Laso)

A giant tortoise in the Galapagos. (Photo by Francisco Laso)

Carolina’s Galapagos Science Center worked alongside the Galapagos National Park in Ecuador to repatriate giant tortoises into the wild. The center’s researchers conducted health assessments on the animals before their release last month.

Close to 30 juvenile giant tortoises in the Galapagos Islands made their way into the wild last month as part of the Galapagos National Park’s breeding and repatriation efforts for this vulnerable species.

Researchers from the Galapagos Science Center, jointly operated by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Universidad San Francisco de Quito in Ecuador, played a vital role in the process by performing health assessments to determine if the juvenile giant tortoises were healthy enough to be released into the environment.

“We’re screening these tortoises to see if they’re good candidates to go in the wild,” said Greg Lewbart, an adjunct professor in the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health’s environmental sciences and engineering department, and a professor of aquatic animal medicine at North Carolina State University. “Are they sufficiently healthy to survive and prosper? Might they be transporting something from the breeding center into the wild? That’s a big thing we want to prevent, and why the assessments are so important.”

The assessments are a crucial step in the release of any animal, but especially the giant tortoise, given their vulnerable status. As many as 250,000 giant tortoises once roamed the Galapagos Islands, but in the 1970s, they were recognized as a vulnerable species when the population declined to just over 3,000 tortoises.

“This catastrophic decline was almost exclusively due to intentional and accidental exploitation by humans, occurring before the Galapagos National Park was formed in 1959,” Lewbart said.

Due to the national park’s effective breeding center on San Cristobal Island and the number of tortoises thriving in the wild, 6,700 tortoises are now alive and well on San Cristobal Island, according to the last census.

Carolina’s and USFQ’s investment in the Galapagos Science Center has enhanced the analytical capabilities within the Galapagos Islands, turning facilities and talents to the conservation and protection of the iconic species.

“Effective management of the Galapagos Islands by the Galapagos National Park is implicitly linked to innovative science being conducted most recently at the Galapagos Science Center. The research at GSC is informed through transformative studies conducted by interdisciplinary members of the UNC-Chapel Hill and USFQ Galapagos Science team, in association with the Galapagos National Park,” said Steve Walsh, director of Carolina’s Center for Galapagos Studies and co-director of the Galapagos Science Center.

Lewbart, who is a member of the Center for Galapagos Studies, is part of an international team of researchers that helped establish baseline health parameters for various species in the Galapagos. Those baseline parameters are used during the health assessments to determine which tortoises should be released into the wild.

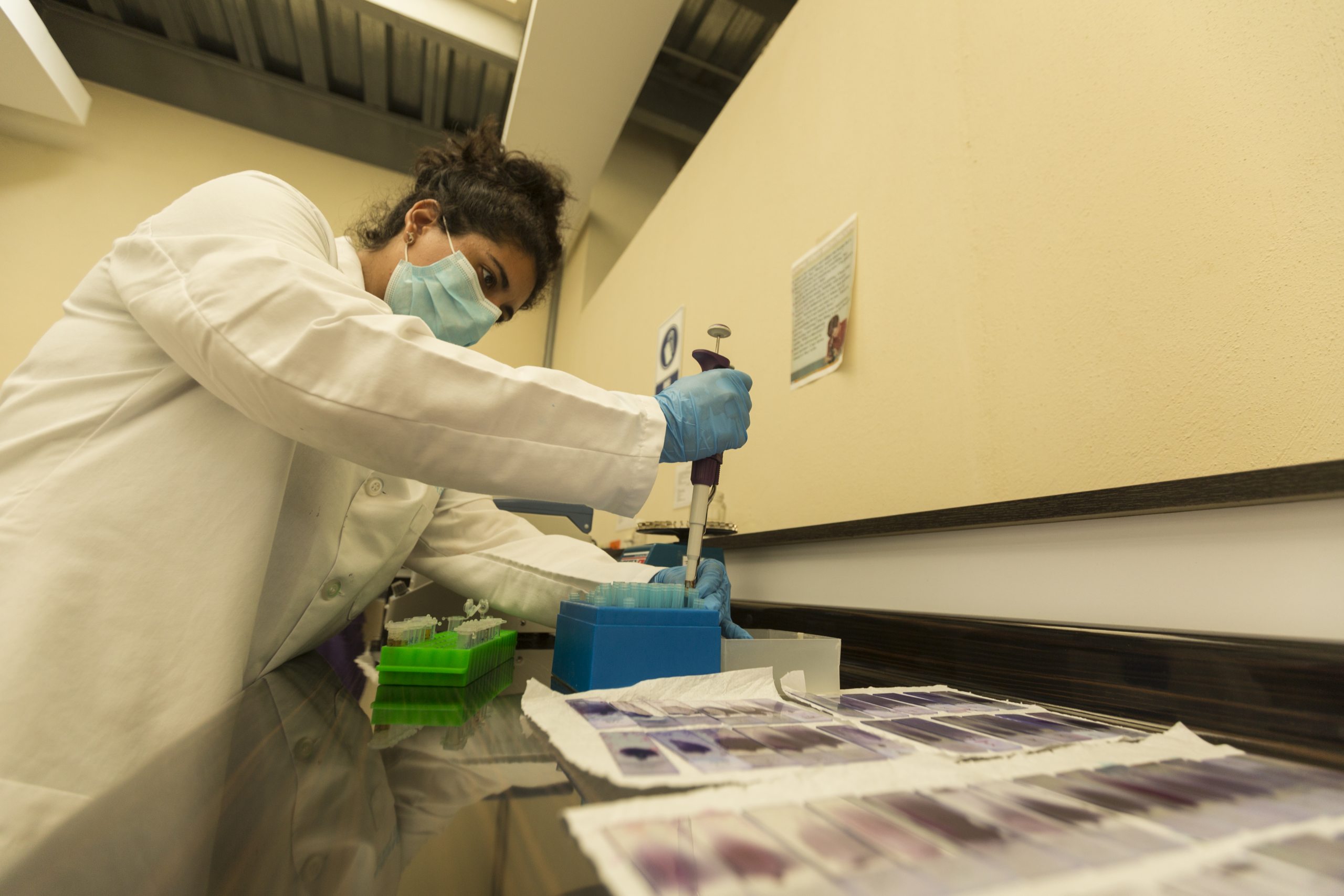

Unable to travel to the Galapagos Islands for this year’s tortoise release due to COVID-19 travel restrictions, Lewbart passed the torch to Soledad Sarzosa, who works full-time at the Galapagos Science Center, managing the microbiology and biomolecular lab.

Sarzosa has led assessments on various species of animals in the Galapagos and has assisted Lewbart in his prior assessments of the giant tortoises, but this month’s release provided a new opportunity to hone her skills.

“It’s a big responsibility to represent the Galapagos Science Center in these health assessments, in collaboration with the Galapagos National Park,” Sarzosa said. “I’m really glad to be a part of it.”

Accompanied by a veterinarian and rangers from the Galapagos National Park, Sarzosa led the team of three Galapagos Science Center researchers to perform health assessments on 30 juvenile tortoises, who are between 6 and 8 years old.

The non-invasive health assessments are comprehensive and include measuring the tortoises’ weights and vital signs, performing blood tests and securing biological samples for future analysis.

“Performing the health assessments are really important because we need to know if the Galapagos National Park is releasing healthy tortoises back into nature,” Sarzosa said. “We need these assessments so the park knows if the juvenile giant tortoises are prepared for ‘real-life’ out in the wild.”

The team divided the work evenly, with individuals taking the samples, while others kept records and made lab slides. Once the samples were taken, the team analyzed some of them on-site at the Galapagos National Park, using Center for Galapagos Studies equipment, while saving some samples for analysis at the center.

Comparing the samples to the baseline health parameters previously established by Lewbart’s team, Sarzosa and the rest of the team determined which tortoises were healthy for release.

“If we didn’t have the Galapagos Science Center, we couldn’t do this research,” Lewbart said. “The center supplies the lab, the freezers, the centrifuges, the relay agents, test tubes and all the stuff you need to do this kind of work.”

After the tortoises are released, rangers with the Galapagos National Park perform a giant tortoise census each year to ensure that they are thriving in their new environment.

With the tortoises now in their new home, Sarzosa is proud of her team and knows that the work they did made a difference.

“All my life I wanted to be a wildlife vet, and now my dream is coming true,” Sarzosa said. “It’s hard work, but knowing that the Galapagos National Park is releasing healthy animals into the wild is something that is in my heart, and I will take that with me every day.”

Learn more about the repatriation